On the first of March 2024, we had our Projections 1 midpoint submission.

In order to understand the process of my work, I will first showcase the status of my submission, following the peer assessment feedback. Then, taking the peer assessment into account and adding more material, I will make changes to the submission as I would have liked to submit it (including the missing process and research explorations).

The fashion modelling world often dazzles with its allure of haute couture and glittering events. Yet, behind the scenes, models face a different reality. Financial instability, objectification, and pressure to meet unattainable body standards are just a few challenges they encounter. Far from the glamorous photoshoots, models often grapple with loneliness, diminished self-esteem, and body dysmorphia amidst the nature of work and the demanding environment of castings.

The mission

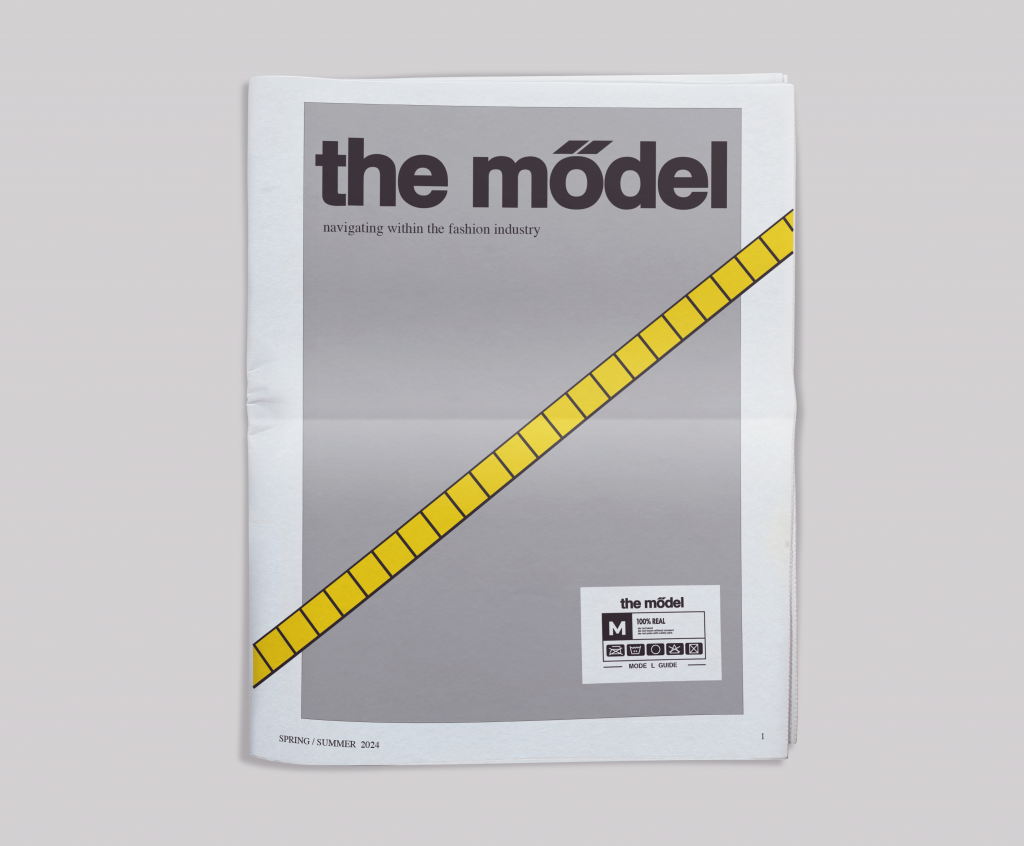

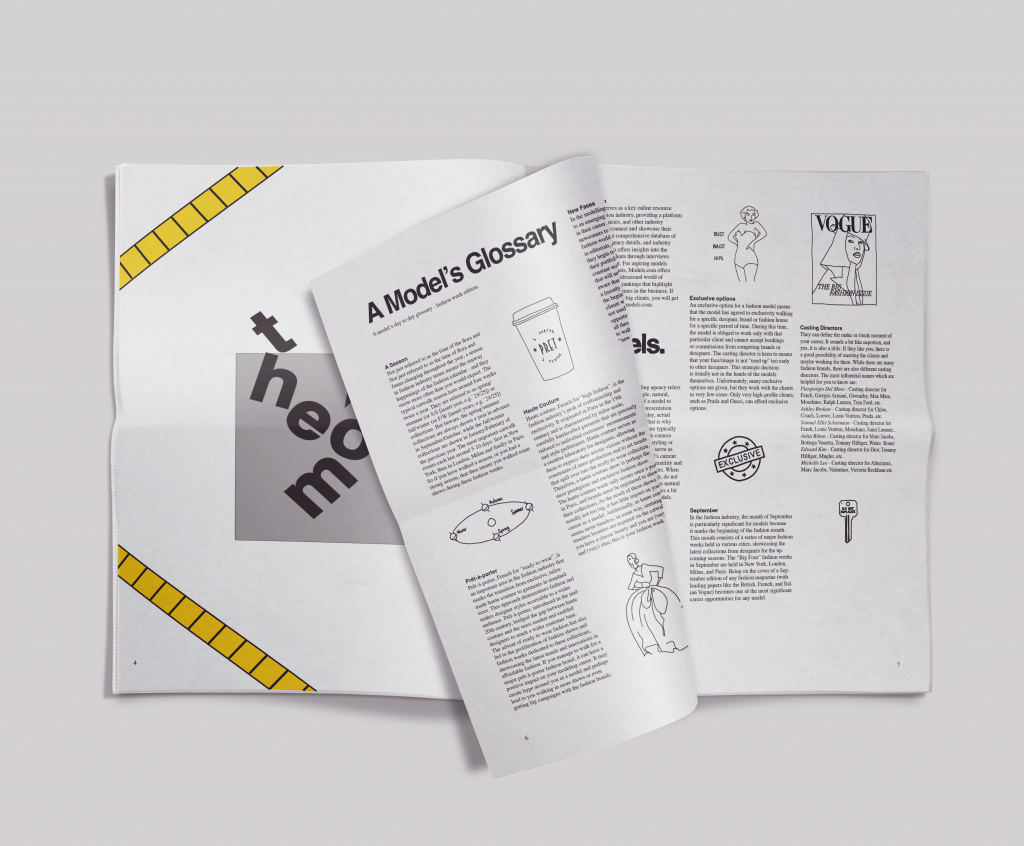

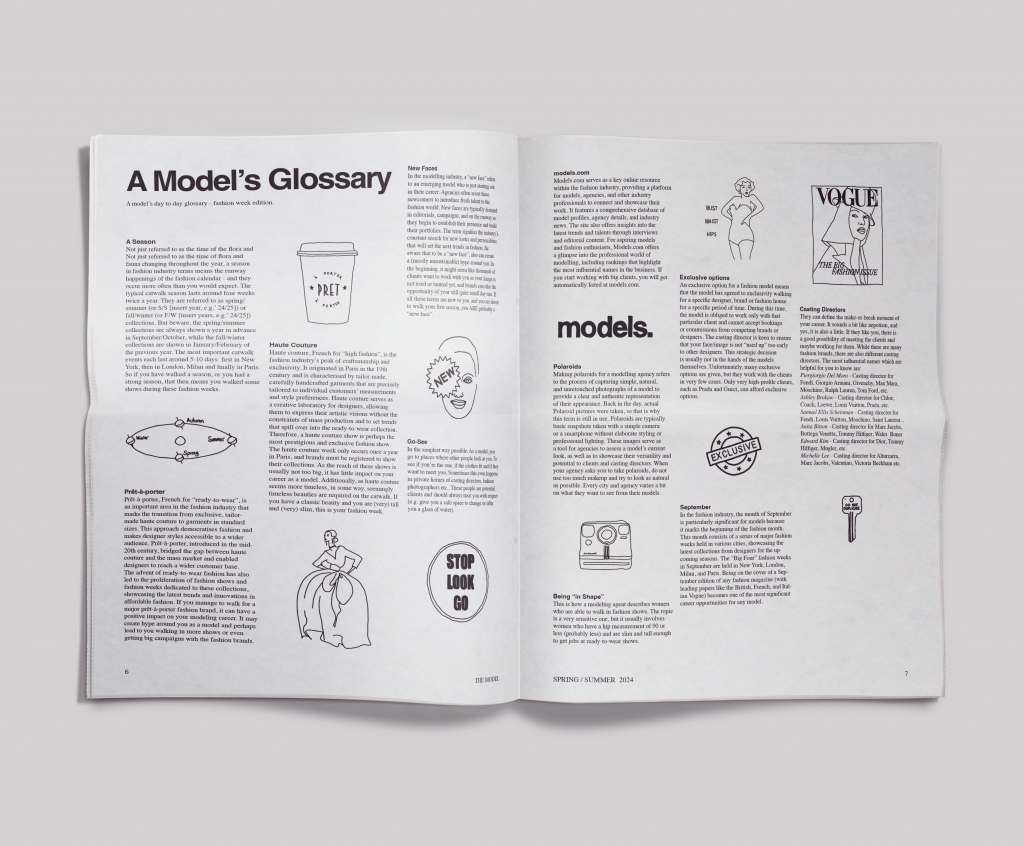

To support models navigating these challenges, I developed a “model guide” in a tote bag—a tote bag is an essential accessory for practically every model, as it is crucial for carrying a portfolio and high heels. This tote contains a newsletter that delves into the critical issues and intriguing aspects of the contemporary fashion scene. It covers topics from navigating the myth of the “perfect size” to practical advice, including a model glossary.

The audience

Targeting primarily the newcomers from overseas who venture into the world of fashion week, “The Mödel” seeks to empower. Fashion week can be the most daunting time, and it’s crucial for them that they find their footing. The goal is to bolster self-confidence, provide essential information, and new ideas among models. This guide is a step towards helping models position themselves in an industry where everything has to fit into a box.

Bibliography

Armstrong, H. and Stojmirovic, Z. (2011) Participate: Designing with User Generated Content.

Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

Fischli, P. and Weiss, D. (1987) The Way Things Go. [film] (No specific publication place or publisher provided).

Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp.575-599.

Herndon, H. (2019) PROTO. [album].

Holzer, J. (1977-1979) Truisms. [LED signs, projections, and enigmatic truisms].

Kruger, B. (1981) Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face. [mixed media].

Ono, Y. (1964) Cut Piece. [performance art] (No specific publication place or publisher provided).

Sherman, C. (1977-1918) Untitled Film Stills. [photography series].

Sontag, S. (1977) On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Feedback

The following document was the feedback I received from my peers:

In my assessment, the reviewers focused on several critical areas: Enquiry, Knowledge, Process, Communication, and Realisation, each of which I received a grade of “Good Evidence.”

Enquiry: The reviewers appreciated my unique approach in exploring the psychological and physical challenges models face, such as body dysmorphia. They found my insights, drawn from personal experiences, both unique and insightful. However, they advised that I could enhance my presentation by incorporating more of my personal narrative and exploring open-ended questions that delve deeper into contemporary fashion issues.

Knowledge: The feedback suggested that I need to include more detailed background information about the fashion and modeling industries. This additional context would help to enrich the audience’s understanding, especially since the page is intended for public display.

Process: The reviewers expressed a desire to see more detailed documentation of how my work evolves and iterates. They emphasized the importance of demonstrating the developmental process of my projects more clearly to give a fuller picture of my creative journey.

Communication: My communication strategy aims to empower newcomers to fashion week, providing them with confidence and strength. The feedback was positive regarding my practical work, which critiques the challenges faced by models. The illustrations were well-received, yet there was a suggestion to include more visual interactions with real bodies to enhance the impact of my guidebook.

Realisation: The potential of my guidebook and the related tote bag was recognized, but the feedback encouraged me to explore beyond these items to diversify the content. They also pointed out the need for a broader representation of model diversity in my work to better reflect the industry’s range.

Overall, the feedback acknowledged the relevance and potential of my work to my career but emphasised the need for a deeper exploration and a broader presentation to fully engage the audience and accurately reflect the complexities of the modeling industry. I really valued their feedback very much and therefore applied a few more insights and process oriented ideas below:

Reflection on Feedback

– the mödel2 –

Let’s start from the beginning:

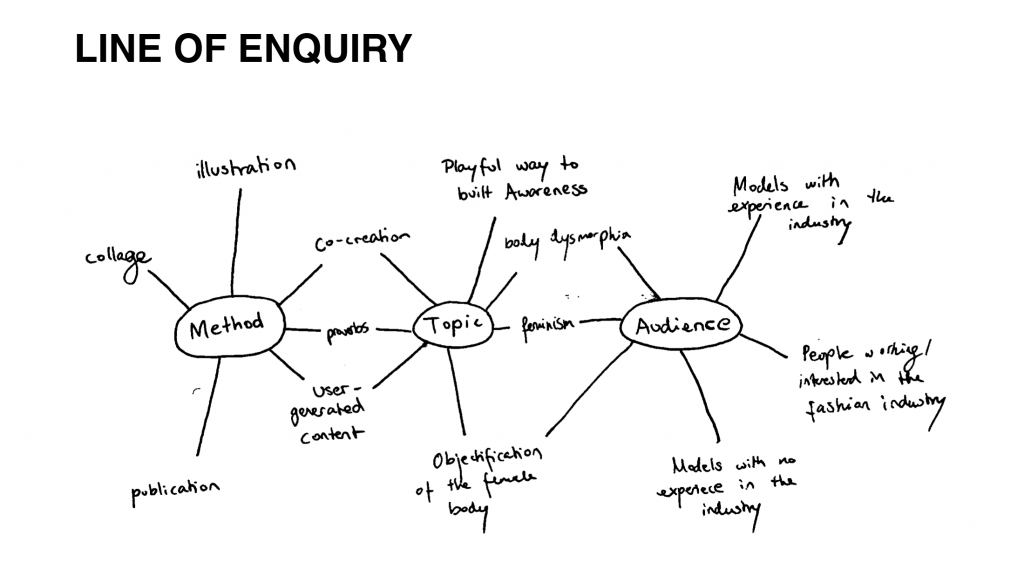

At the start of Unit 3, I reflected on my practice up to this point and noticed my focus on the topic, methodologies and the audiences I wanted to attract. By mapping out these interests and reflecting on my journey as a designer so far, I linked the worlds that I have been dealing with: fashion, design and arts. To narrow it down, I wanted to use my unique positioning by being a (nearly retired) fashion model with more than 13 years of experience in the fashion industry while also being able to apply my understanding of graphic communication design.

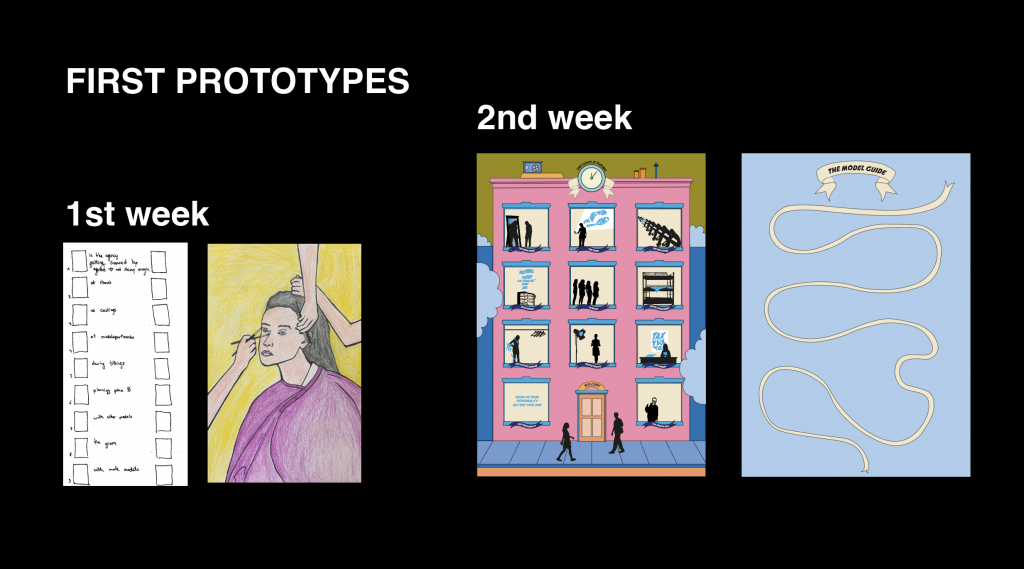

Initially, I opted to use illustration as my primary medium to depict the experiences of fashion models, including my own, to raise awareness of the inherent struggles. However, the illustrations felt inherently biased and misaligned with my intentions. Despite using baby blue and pink illustrations to critique these biases, I inadvertently reinforced the stereotypes I intended to mock.

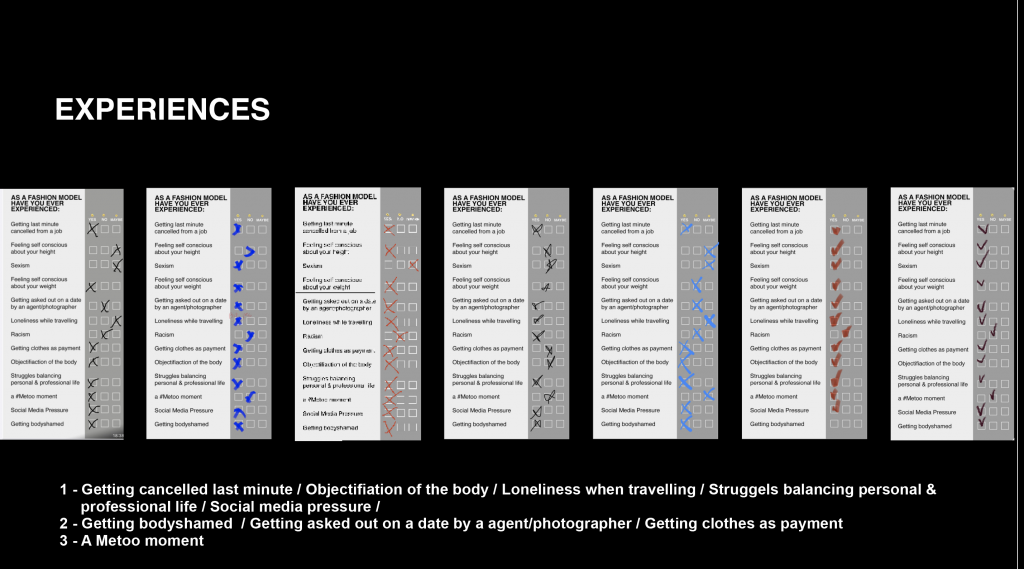

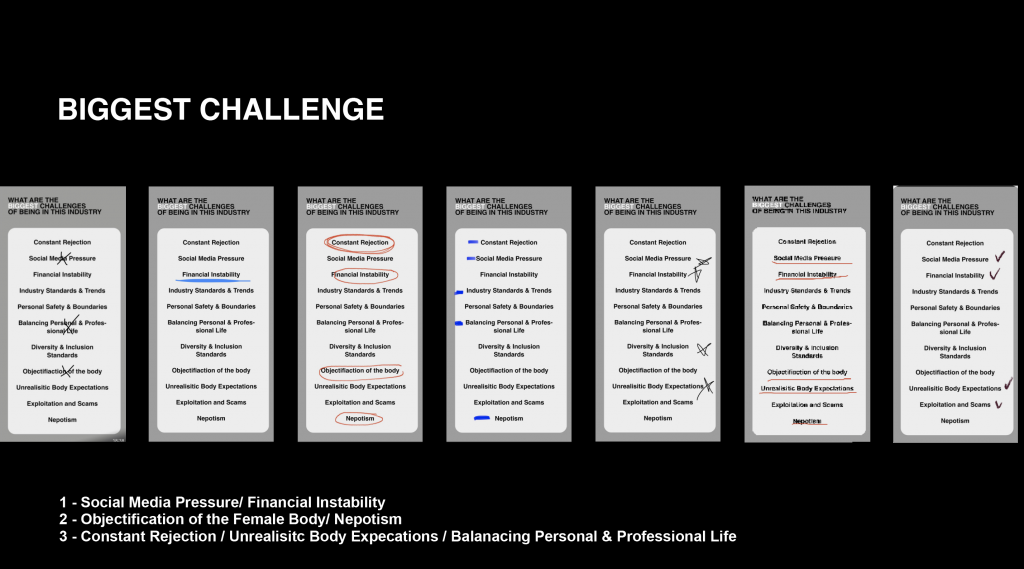

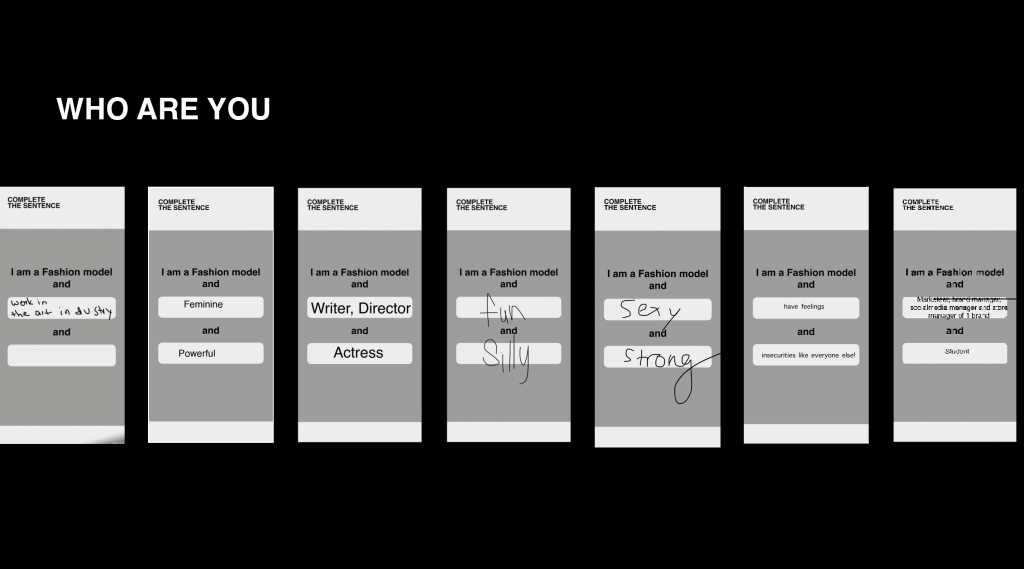

So, I pivoted my practice by making my design choices more user-generated. I used a very mundane-looking template to spread a questionnaire via social media to my fashion model colleagues. The questions were quite revealing about how challenging the industry can be. Very interesting was the way the models responded as everyone had a very individualistic way of crossing, underlining, or highlighting their answers.

From then on, I collated more evidence through interview and thought about ways to illustrate them visually. It turned out to be very challenging to talk about the multitude of challenges and traumas that I eventually heard from my colleagues.

One problem that came up a few times between the lines, and I have experienced myself as a fashion model, is people’s biases about this profession. Having often concealed my job due to the preconceptions of being a fashion model, I was interested in exploring these prejudices further.

Delving deeper into my feelings of shame (because of societal expectations), hypocrisy (I consider myself a feminist yet deliberately chose to be objectified) and insane privilege that I felt for most of my career, I was curious to find out what an AI model had to say about models. Would it be as sexualising, objectifying and offensive as a random heterosexual man can be who just heard you are a model? If an AI model somehow reflects most people’s opinions on the internet, wouldn’t it also reflect public opinion about fashion models?

This exploration turned into a publication further explored in another blog post HERE. While I have started to view AI models as strong collaborators for projects to speed up processes, this helped me view the Chat GPT from a more critical angle. In the end, the experimentation showed a very biased depiction of female models. This—to be fair—was not a big surprise to me.

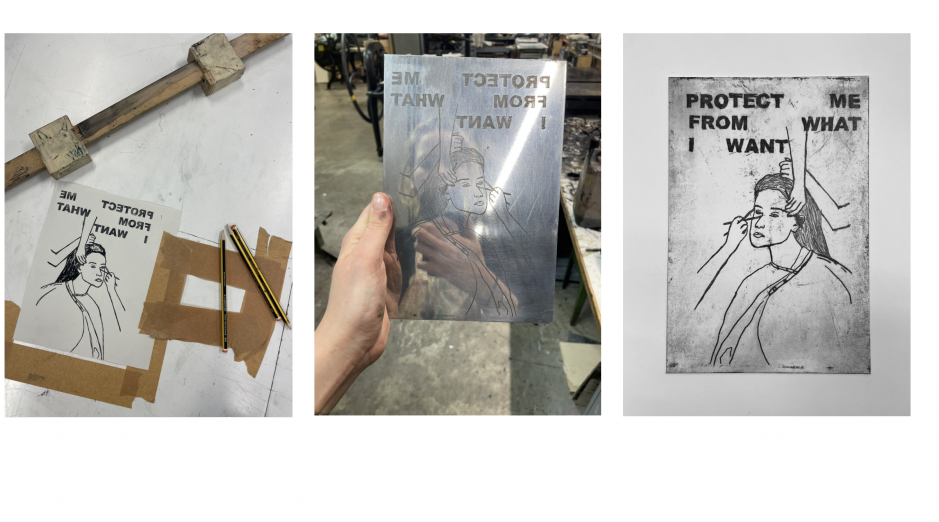

My research then expanded to include female artists and designers addressing body image, proportional studies, forms, and visual identity issues. My extensive research helped me overcome the apprehension about using my body image in my work. In one experiment, I etched the phrase ‘Protect me from what I want,’ a quote by Jenny Holzer, across my set card (a set card is like a model’s business card containing essential descriptors such as your measurements, hair and eye colour).

This experience brought me back to the concept of user-generated design – I did not want this project to be only about me. Therefore, I created an AR filter to give users the appearance of being in a fashion campaign. However, this experiment fell short as it did not fully convey my intended message.

Returning to the knowledge I had amassed, I reflected on the myriad challenges fashion models face and how these influence societal perceptions of the female body. I asked myself: Doesn’t it all come back to sizing again? These explorations then led me to generate a newspaper that would not only educate about specific fashion model terminologies but also function as a way to reflect on the evolution of ideal female body types. Eventually, I hoped that this piece would be thought-provoking about characteristic fashion industry standards and make people rethink their need to fit in (size 0).

Note to the reader: Start reading from the beginning again